Simone de Beauvoir and the Courage Women Writers Need

On Facing our Fears and Blazing New Trails

“The writer who is original, as long as she is not dead, is always scandalous; what is new disturbs and antagonizes; . . . she does not dare to irritate, explore, explode.”—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

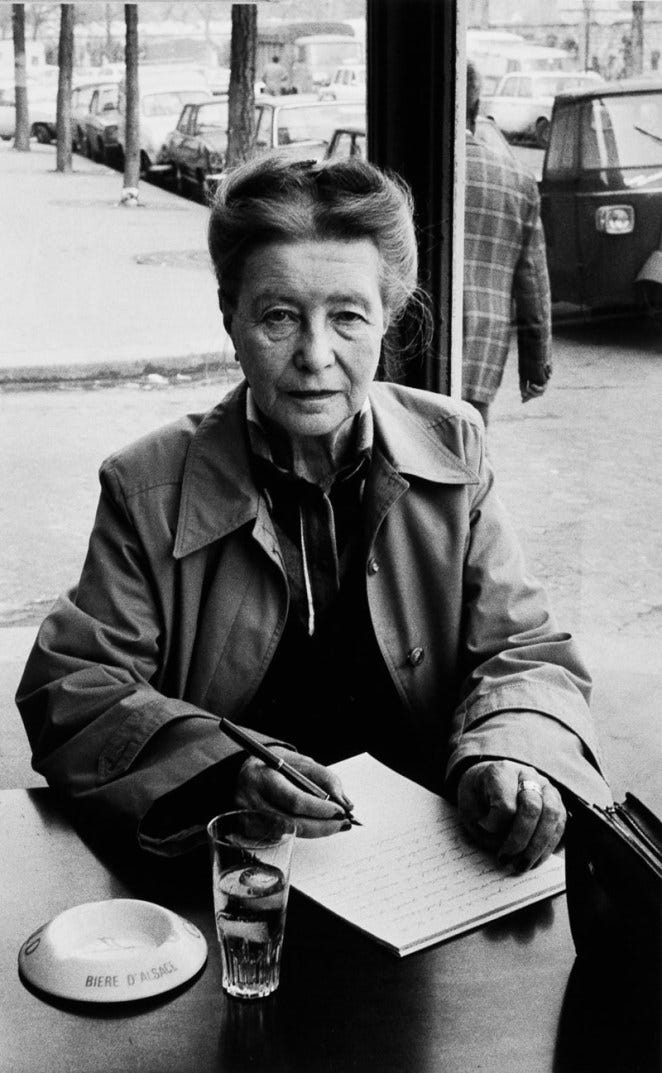

Simone de Beauvoir was incredibly audacious—in her writing and her life. She was a complicated woman (who made some choices in her private life that we might question), but she was also complex and incredibly brave. I won’t be writing her about her relationships with Sartre and her many other lovers. I want to focus on her thoughts about writing, how hard it was to be a woman writer, and what women needed to be writers.

Beauvoir has languished for decades in Sartre’s shadow. In the words of her biographer Kate Kirkpatrick, “Beauvoir has not been remembered as a philosopher in her own right.” (Her book, Becoming Beauvoir, set out to change that.) When Beauvoir died, obituaries described her as a “popularizer” of Sartre’s ideas, “Sartre’s female intellectual counterpart,” his “disciple,” and “incapable of invention.”

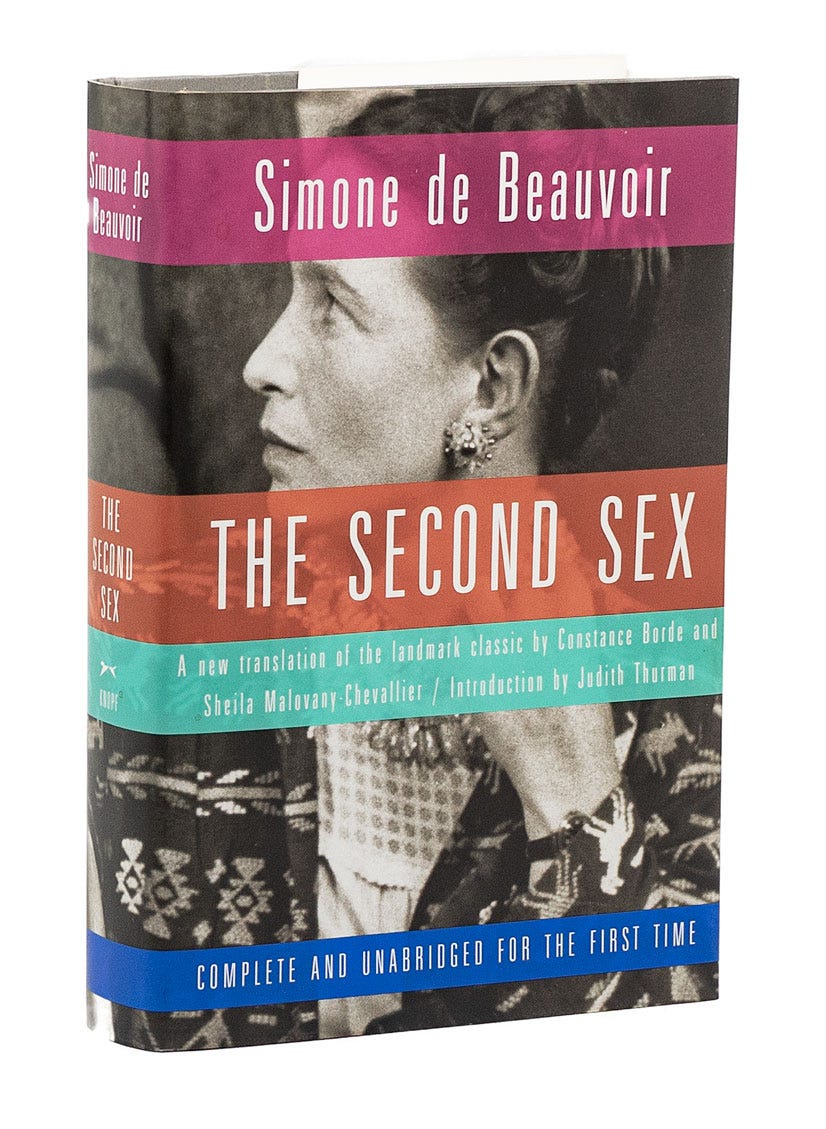

Yet Beauvoir developed many of her important ideas before she even met Sartre, and she disagreed with him on many points. Sadly, her most important work, The Second Sex, was badly (mis)translated into English in the 1950s by a male zoologist who had no knowledge of philosophy or feminism and who cut many passages out entirely. An authoritative translation of the full text finally appeared in 2009. Yet, the old one floats around like driftwood. When I read the book last year, I was part way through before I realized I was reading the 1950s edition. So, reader beware!

Beauvoir as a Writer

Beauvoir had always wanted to be a writer, but she grew up with the view that women could not be original or contribute to literature what men could. While a student, in the 1920s, she read Schopenhauer’s views on women, whom he called “the second sex, inferior in every respect to the first.” As far as their abilities to be writers, he wrote, “Women have great talent, but no genius, for they always remain subjective.”

She had to look elsewhere for stories of young women that could be mirrors to hold up to herself or, as biographer Ursula Tidd puts it, “ballast against her own isolation.” She knew she wasn’t like other girls and found kinship in Jo March and Maggie Tulliver, in particular. Later, her own writing would provide the same function for female readers eager to understand themselves—a bulwark against the Schopenhauers of the world.

For Beauvoir writing, particularly in her journals and later in her published memoirs, was the vehicle of self-understanding. She was constantly dissecting her life, analyzing it, and using her solitude to understand herself. More than that, she “wanted to vivre philosophiquement—to live a thinking life, rather than to just live, [or] to just think—and to write out of the riches she felt welling up within her” (Kirkpatrick, Becoming). Yet to do so and actually publish that writing meant to draw critique, ridicule, and sometimes blatantly offensive remarks from reviewers. “In France, if you are a writer, to be a woman is simply to provide a stick for you to be beaten with,” she once wrote (quoted in Tidd). She was often attacked as a woman rather than taken seriously as a writer.

Her novels also drew on her life, leading many to dismiss them as autobiographical and somehow less worthy. The Mandarins (1954) won the Prix Goncourt, yet was (and still is) described as a roman à clef. Yet she insisted that “it was truly a novel. A novel inspired by circumstances, by the postwar era, by the life I knew, by my own life, etc., but really transposed on a totally imaginary plan widely straying from reality” (“A Story I Used to Tell Myself,” 1963, in “The Useless Mouths” and Other Literary Writings). The fusion of life and art has always fascinated me, and of course it is most often women writers who are accused of, or taken to task for, drawing on their lives in their fiction, as Beauvoir was.

Beauvoir on Women Writers

In “The Independent Woman,” the final chapter of The Second Sex, Beauvoir has a lot to say about the state of women’s writing in 1949. It doesn’t start out well.

It is well-known that she (the woman writer) is talkative and a scribbler; she pours out her feelings in conversations, letters, and diaries. If she is at all ambitious, she will be writing her memoirs, transposing her biography into a novel, breathing her feelings into poems.

Ha!—all of which Beauvoir herself did. (She wouldn’t publish her first volume of her memoirs until 1958.) She also laments the “timidity” of women writers and artists:

Her (woman’s) great concern is to please; and as a woman she is often already afraid of displeasing just because she writes; . . . she lacks the courage to displease even more as a writer. The writer who is original, as long as she is not dead, is always scandalous; what is new disturbs and antagonizes; . . . she does not dare to irritate, explore, explode.

Exploding is what women writers need to do, apparently. They must be willing to irritate and simply piss people off. Beauvoir certainly did that with The Second Sex and parts of her very frank memoirs, yet since her death, as new letters appear, it has become clear that she didn’t have the courage to reveal everything about her life. (See Kirkpatrick, “Was Beauvoir . . . ?” linked below.)

We’ve come along away from the “woman” of 1949 as Beauvoir describes her, but this need to please—I think it’s more than a desire—runs deep in us. We want to be liked and receive praise not because we are simply timid but because our survival has depended on it. And even if it doesn’t currently for many of us (although for many it still does), that legacy of women’s financial and existential dependency on men runs deep. It won’t go away in a generation or two.

Such lack of courage, or fear of rocking the boat, leads to conformity, rather than originality (if that is even possible anymore, I hear you murmuring). The result of trying to please, of seeking critical approval, as Beauvoir describes it, is that women writers “will not abandon themselves to the contemplation of the world: they will be incapable of creating it anew.”

Further, “She will imitate rigor and virile vigor.” This reminds me so much of Claire Vaye Watkins’s admission in her viral essay “On Pandering” (2015) that she had watched and imitated men because that was what being a writer was—until she had a child and found that she could no longer write this way.

The timid woman writer will not “blaze new trails,” Beauvoir says. It’s not that women lack originality (as she was raised to believe), but that they lack the courage to be original. “Women do not lack originality in their behavior and feelings,” she says. In fact, “there are some so singular that they have to be locked up.” Ultimately, she says that “no woman has ever thrown prudence to the wind to try to emerge beyond the given world.”

Like Virginia Woolf, whom she cites, she argues that women writers have been hampered by having to justify their existence, to strain against the prejudices against women as writers and the conventions that circumscribe women. And so long as they feel to need to do so, they will never push beyond “the given world.”

She also quotes the artist Marie Bashkirtseff, who lamented that in the 19th century she didn’t have the freedom to walk around alone. Without solitude and an “original relation to the universe” (as Emerson put it), a woman cannot be a true artist or writer. The reason there has been no female Kafka or Tolstoy or Rousseau is because of the situation or historical conditions in which women live, she says, not “some mysterious essence. The future is wide open.”

The future is still wide open. It’s an exciting time for women, and for women writers, as we tell the stories that have been buried for so long and proclaim “Me Too” or dare to challenge the image of the all-sacrificing, always-content mother. But these stories are still hard to tell. One of my favorite quotes is from Muriel Rukeyser’s poem, “Käthe Kollwitz”:

What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?

The world would split open

Has it split open, I wonder? Or is it just starting to crack? And are women’s stories really that powerful? Or important?

I could go on and on, but I want to hear what you think. Do you think women (writers) are often still hampered by the desire/need to please? Are we still afraid at times to cross the boundaries of what is acceptable? Have the conditions arisen for women to be the kind of writers and artists that Beauvoir imagines here? Who are the women wrtiers today “throw[ing] prudence to the wind” and blazing new trails or creating new worlds in literature and art? What resonated with you? Or what perhaps, ticked you off? I’m dying to know!

As always, you can simply reply to this email to share with me alone. Or you can engage in the comments online (just click Comment below).

And if you’d like to participate in the “Meet and Greet” thread I sent out last week, you can do so anytime. Feel free to pop in there and introduce yourself and see who else is here and what cool stuff they have been reading by/about/for audacious women leading creative lives.

See you in the comments—or the next time I pop into your inbox,

Anne

Further Reading

Simone de Beauvoir, “The Useless Mouths” and Other Literary Writings

Kate Kirkpatrick, Becoming Beauvoir: A Life

Kate Kirkpatrick, “Was Beauvoir as Feminist as We Thought?”

Ursula Tidd, Simone de Beauvoir

Claire Vaye Watkins, “On Pandering”

“In France, if you are a writer, to be a woman is simply to provide a stick for you to be beaten with,” Wow!!! So powerful. And the summary-annotation from you as well, Anne—that women NEED to please, which can keep them from doing radical work. So much the case for the three women at the center of Engaging Italy, as I noted in those pages. Thanks for another insightful piece.

Super interesting, thanks! Was familiar with Simone de Beauvoir's story, but not the Tin House article and that was an interesting combo. Loved how you pulled different threads together. Claire Vaye Watkins's piece made me think quite a bit. I think that some of that background was why I focused on the scene of an interviewer being awestruck by Yoko Tawada, in an essay here on Substack about Tawada's book about a vanished language. It actually felt unusual, and that was shocking. On the other hand, I don't share Watkins's experience when it comes to fiction. I think I got shocked out of it when I first got to attend literary readings as a teenager and discovered that I didn't like John Updike's writing or how he read it, even though he was in the New Yorker. The same with a couple of other writers. It changed the world on its axis a little.