Audacious Women, Creative Lives is a newsletter sharing inspiring stories of women writers and artists, as well as a community supporting and inspiring women to live bold creative lives.

“Someone out there should absolutely make a female genius biopic about Suzanne Valadon,” --Caitlin Horrocks, author of a novel about the composer Erik Satie, one of her lovers

I agree with Caitlin Horrocks—for several reasons, but primarily these three: 1) Suzanne Valadon was an incredible artist, despite having received no formal training. 2) She broke just about every taboo as a woman and an artist. 3) She deserves to be known as a serious artist, not just as a model for the great male artists.

I first became aware of Suzanne Valadon when I stumbled across her at the Musée de Montmartre in Paris during the first few days of my travels, in September 2022. Although she is not as well known as other female Impressionist and Modernist painters, she has a special place there at the museum, in the rue Cortot, where she herself lived from 1912 to 1926, purportedly her happiest years.

Remarkably, her apartment and studio—which was often visited by the artists who flocked to Montmartre during those years, such as Raoul Dufy, Georges Braque, and Amedeo Modigliani—have been preserved as part of the museum. It is quite an experience to walk back in time as you enter the bright studio.

Who is Suzanne Valadon?

Valadon was born illegitimately in 1865 to a laundress and seamstress. She grew up in Montmartre, a working-class village on a hill above Paris, where artists gathered and cabarets flourished. After five years of working odd jobs, including as a trapeze artist, she became a model at the age of sixteen for Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and other artists. Valadon was the model for some of Renoir’s most famous paintings, including La Danse à Bougival (1883).

The same year she appeared in that painting, at the age of eighteen, she also gave birth to an illegitimate son, Maurice, who would be acknowledged by the artist Miguel Utrillo eight years later, although it is believed he did so as a friend, not as the biological father. Suzanne never said who the father was.

Her years as a model were also her apprenticeship as she learned from the artists how to paint and develop her drawing, which she had been doing since she was as child. With the encouragement of Edgar Degas, who bought some of her works, she turned from model to artist. In 1894 she became the first woman to exhibit at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, where she was listed in the catalog as Valadon, S.

But she would step back from painting and exhibiting in 1896 to marry and focus on raising her son, whom she encouraged in his own budding career as an artist. (Maurice Utrillo would go on to become a famous artist, overshadowing his mother.) Thankfully, her story doesn’t end there.

By the time she was forty-five, Suzanne had had enough of bourgeois life and moved back to Montmartre, taking a younger lover, André Utter, an artist himself and also a friend of her son’s. This is when Valadon’s career really took off. She exhibited frequently in the 1920s and 30s and had four major retrospective exhibitions. She painted still lifes and landscapes but was particularly known for her female nudes. Her bold brushwork and vibrant colors were much sought after, and her work can be found today in many of the world’s major art museums.

Why Is Valadon Not Better Known?

“Despite her formidable talent, Suzanne’s reputation as an artist was, until very recently, clouded with tedious moralistic judgements about her virtue, or rather, her perceived lack of it.”—Jennifer Higgie “How Suzanne Valadon Reclaimed Her Image By Painting Herself Naked”

Suzanne’s life was full of reasons for raised eyebrows. And then there was the art, which broke as many taboos as her life did. But it’s for precisely that reason that her art should be valued today. Suzanne Valadon’s boldness should have paved away for later women artists, but she faded into relative obscurity, while her son remained well known. Her daring canvases remain audacious today, particularly for their sensitivity to and celebration of the female gaze.

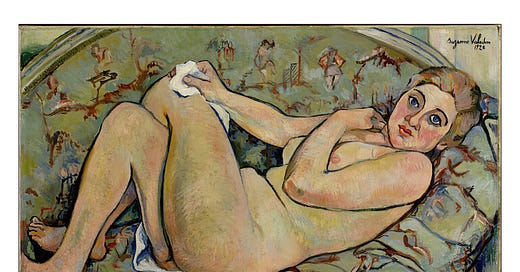

When she painted the reclining female nude, a stock figure in Western art, she introduced a new perspective—a woman’s. These works exhibit a deliberate attempt to enter into a tradition of famous male artists’ portraits of nude women (Titian, Eduard Manet, et al.) yet display the double consciousness of the female artist/model, who is both seen and sees, an object of desire and a subject aware of being objectified. Comparing her work to the famous reclining female nudes by Titian, Ingres, and Manet, Lauren Kraut argues that Valadon “reclaimed the female nude.” (This is really worth a click-through to see the paintings all side-by-side.)

In her most famous female nude (above), the figure looks straight at the (male) viewer with a look that has been variously characterized as indifferent, defiant, and uncertain. Valadon refused to idealize the female body. She painted skin with raw patches of blue and green tones, instead of alabaster smooth, and did not erase the nipples or pubic hair. The poses are often natural, even awkward, rather than alluring.

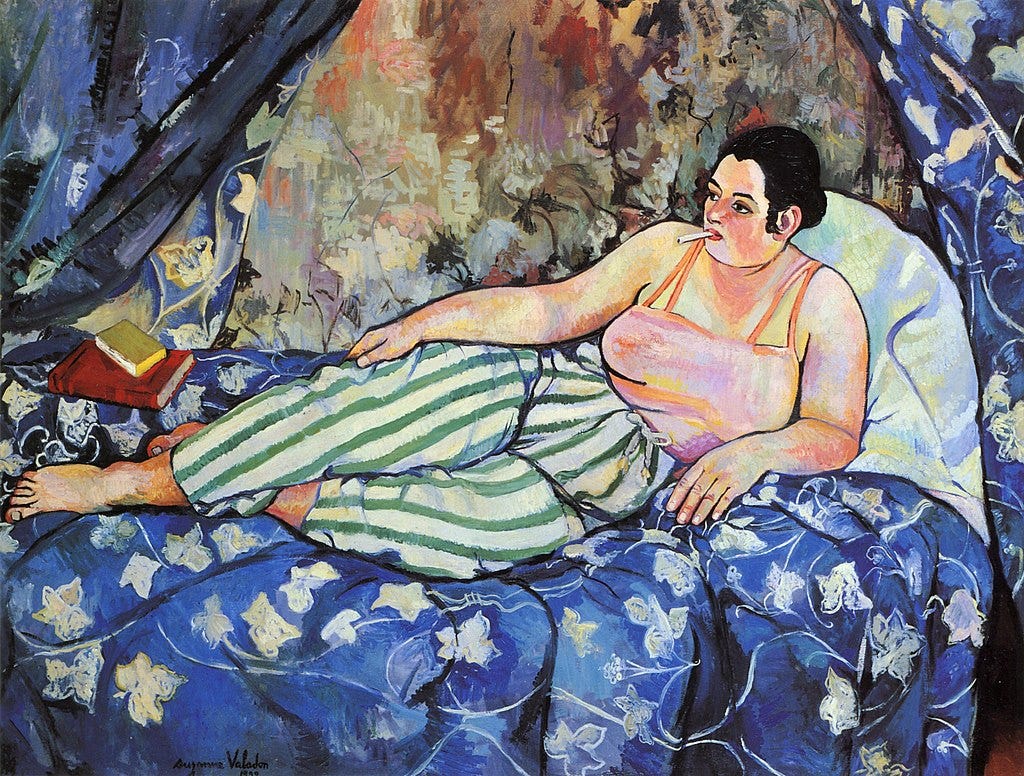

In “The Blue Room,” perhaps her most famous work, the female figure (whom many say is Valadon herself) is again reclining, but with a difference. She defies the viewer by refusing to look at him and by remaining clothed. Yet she exudes her supreme comfort in her own skin. (This woman clearly doesn’t give a f***.)

Portraying the Male Body

When Valadon met André Utter, they began using each other as models. With her Adam and Eve (1909), she became the first woman known to paint a nude couple, portraying herself and Utter. The moment captured is before they ate the apple, highlighting their innocent beauty. Valadon had painted Adam completely nude but in order to show the work the Paris Salon, she covered his genitalia with fig leaves.

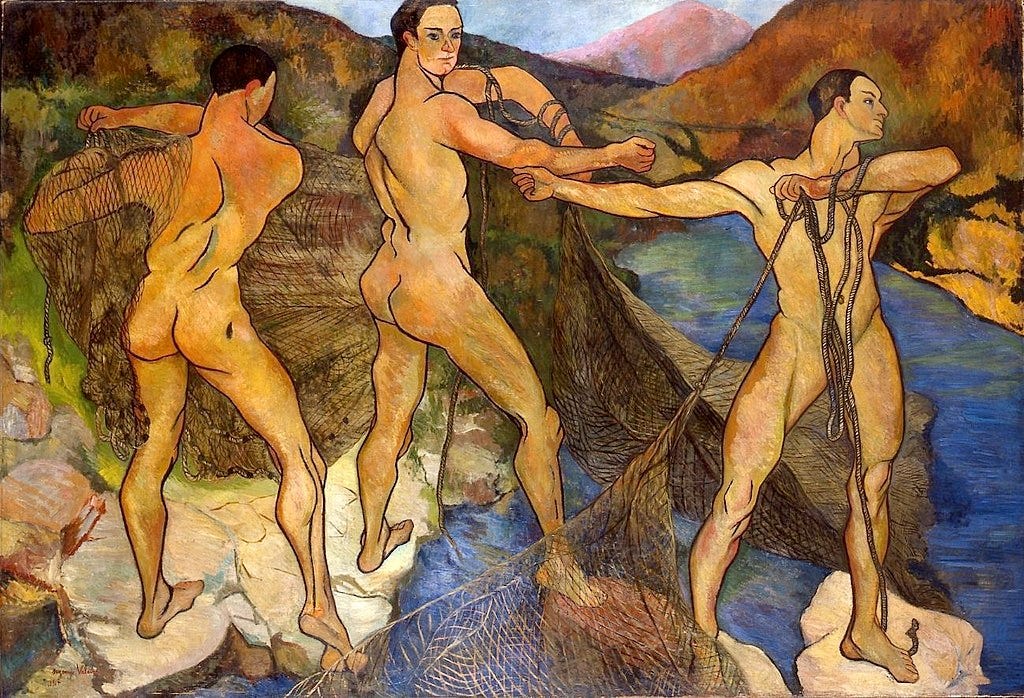

Her monumental “Casting a Net” is another rare example of a female painter’s depiction of the nude male body. Again the model is Utter, whom she studies from three angles. The result is a “luscious and sensual treatment of the male nude,” writes Lauren Jimerson, an object of the “eroticized gaze of the heterosexual female artist.” Valadon dared to objectify the male body, celebrating its athletic beauty, as her own body had been objectified by male artists.

It was almost unheard of for a woman to paint the male body. Keep in mind that it was incredibly difficult for women to receive instruction in drawing or painting from life. When they did, naked men were not on the program. Female art students were offered unclothed women or clothed men.

Valadon had the temerity to not only paint the male nude and to convey desire for the male body, but also to exhibit this work. It seems critics were so shocked they just pretended that it didn’t exist. While they lavished considerable ink on her female nudes, they were mum on her portraits of the male nude, says Jimerson. This silence has persisted ever since, she says, and in fact, I had a hard time finding out much about them.

I could find only one earlier woman artist, Giulia Lama, from the late 1600s, who dared to draw and paint the male nude. Today, women still rarely paint or draw men’s bodies. The artist Jane Clatworthy has some very interesting things to say about women’s reluctance to paint the male anatomy and their tendency to turn the gaze on themselves instead.

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments. Are you familiar with Valadon’s work? What do you think of it? Do you know of other women artists who were daring in their portrayals of female and/or male nudes? Why is it so difficult for female artists to turn the gaze on male subjects? How important is it that they do so?

See you in the comments!

Anne

“Audacious Women, Creative Lives” is a newsletter sharing inspiring stories of women writers and artists, as well as a community supporting and inspiring women to live bold creative lives. Do join us! Or consider offering your support.

Anne, what a pleasure to wake up with this revelatory introduction to a neglected trailblazer. I particularly appreciated your discovery of Valadon’s male nudes. Thank you.

Fabulous. I didn't know this artist, and she is very fine. Thank you for the intro and for opening a question I hadn't considered: the male nude, especially as painted by a woman. I'm sorry she felt she had to hide the genitalia. Adam and Eve makes no sense as Eve reaches for the apple and Adam is already figged. I'll be reading more about Valadon. The old story: a woman's "morals" work against her, but a man's art remains the focus. Good work you're doing here.