“Lee Miller was a woman the twentieth century needed to create—independent, liberated, creative, courageous and multi-talented—but she was her own remarkable invention. Her extraordinary career as an artist defies stereotypes. Despite being increasingly admired and studied in recent decades, she remains a ‘surrealist puzzle.’”—from the Introduction to The Art of Lee Miller

This newsletter is free for all. Sign up so you won’t miss a post.

Hello! I’d like to share some of my thoughts about Lee Miller this week, as I’ve been spending some time with her lately and have long been interested in her.

It’s been a very busy two weeks since classes started in my new MA course in Creative Writing. I’m struggling to keep up with the pace of reading, writing, and providing feedback to my fellow classmates on their writing. As a result, I am so behind on perusing and responding to your comments on the past couple of posts that I don’t know if I’ll ever catch up. I’m sorry that I can’t be as active in the comments as I’d like to be. But I hope that you find the interaction with other Audacious readers rewarding. I’ve been so amazed at how generous, encouraging, and downright fascinating you all are! I miss connecting. Hopefully I’ll have more time as I settle into my new schedule.

As I’m sure you’ve noticed, Audacious Women, Creative Lives has been morphing, as my newsletter itself has over the past eight years. I’ve started a series of “Life 2.0” posts about what I’ve learned during my huge life transition. And I’ll be sharing more about what I’m learning in my course as well. A big part of my journey has been leaving academia to write creatively. So I’ll take you along with me on that journey as well.

The first unit of the fiction workshop I am taking is on structure. I have a story I would like to tell, and I’ve thought a lot about characterization and historical background, etc., so it’s interesting to begin the class by thinking about how to structure a story. (I’ve found John Yorke’s Into the Woods a particularly helpful resource, by the way.)

One of our first assignments was to revisit a favorite novel that is similar to the one we’d like to write and make a list of its main plot points. The novel I reread was The Age of Light by Whitney Scharer. Have you read it? I did when it first came out, and I was enraptured. I was reading it then purely for pleasure, as I do pretty much all contemporary literature. Only now am I starting to read with an eye to how these novels are constructed.

So what had grabbed me on that first reading? First and foremost the content. It’s a story about the model-cum-photographer Lee Miller. Do you know her? She is utterly fascinating. And perhaps you’ve heard about the just-released film Lee, starring Kate Winslet. I saw it over the weekend. It starts slowly and misses some opportunities to create a fuller characterization of her, but I was gripped from the point that she went to war. It gave me an immense appreciation for what she and other war correspondents and photographers endured to make sure that WWII was documented and never forgotten.

But more about The Age of Light: It’s about her relationship with the artist Man Ray from 1929-1932, when she was his assistant, muse, and lover. From him she learned how to take and develop the photographs she wanted to make. They discovered solarization and other techniques together and had a passionate love affair. But when he became possessive, she left him and started her own photography studio. “I would rather take a photograph than be one,” she once said.

What I particularly love about Scharer’s novel is how it intertwines the stories of her love affair with Man Ray and her development as an artist. We see her growing sense of herself in love and art, two intermingled strands that ultimately come unraveled under the great tension between these two figures: the older artist who has established his own style and practice and the younger muse who is struggling to be her own individual self.

The novel is also beautifully written, full of sensual details and moving passages describing Lee’s interiority. The prose is often simple and direct but manages to convey so much about art and complicated emotions and power dynamics. Here is a moment I love:

“One Rue Pierre Lescot, Lee stops and works to calm her breathing. She holds her camera in both hands and feels as though it is bonded to her skin and completely connected to her. Getting the shot has erased Man from her mind and hinged her to the present. The people, passing by her, appear in flashes, a film reel unspooling as she walks. She heads back toward Les Halles. The street is crowded. Lee watches the lives around her and begins to come back to herself—or to come to herself for the first time. Her eyelids are like a camera’s shutter snapping; she blinks the motion around her into pictures. Every once in a while, one of the pictures she creates in her mind is worth saving, so she picks up her camera and freezes it on film. Every picture she takes feels alive and unexpected. And Lee herself feels more alive than she ever has, just taking them.”—Whitney Scharer, The Age of Light

And I have to mention the sex scenes. They are beautifully written as well. Scharer said in an interview that those were the hardest to write. She absolutely gets them right, making them integral to the novel’s larger themes.

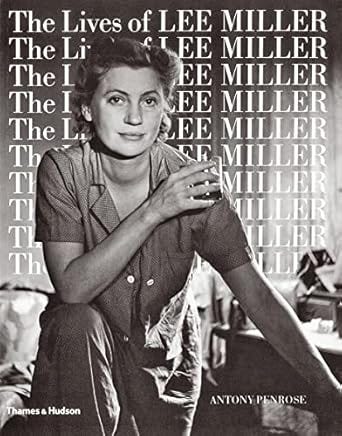

I heard Scharer say in an interview that she began writing the book after seeing an exhibit about Ray and Miller in 2011 at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA. Although she had majored in art history and had a particular interest in photography, she had never heard of Miller. Certainly Miller suffered from the neglect that so many women artists have suffered. But I’ve learned that she also participated in downplaying her photography career, particularly the work she did during WWII, when she was war photographer for Vogue, in whose pages she had appeared for years as a model and then as a photographer.

According to a Guardian article from 2016:

“When she was alive, Miller successfully convinced everyone that she hadn’t done anything worth talking about. Tony [Penrose, her son,] says that when anyone asked her about her time as a war correspondent for Vogue magazine, she would say: ‘Oh, I didn’t do much, it wasn’t of any importance and it’s all been destroyed since.’”

I was recently interviewed by the writer Iris Jamahl Dunkle for a piece she is writing about the challenges of writing women’s biographies, and one of the things we discussed is how many women in the past have hidden or destroyed their own pasts—for a variety of reasons. For many, I suspect that they viewed their creative lives as separate from their personal lives, as something they maybe even had to set aside when they settled down, so to speak. Perhaps it was even painful to remember what they had given up, a part of themselves they maybe weren’t able to fully realize.

She said near the end of her life, “Nearly all the photographs I ever took have disappeared—lost in New York!—thrown away by the Germans—in Paris—bombed and burned in the London blitz—and now I find Condé Nast has just casually scrapped everything I did for them, including war pictures.” (Quoted in The Lives of Lee Miller, by Anthony Penrose.)

But she also packed away her photographs and writings and put them in the attic. Her son knew almost nothing about her career, discovering only after her death 60,000 photos and negatives in the attic Shocked by what he uncovered, he created the Lee Miller Archives to honor and preserve her legacy.

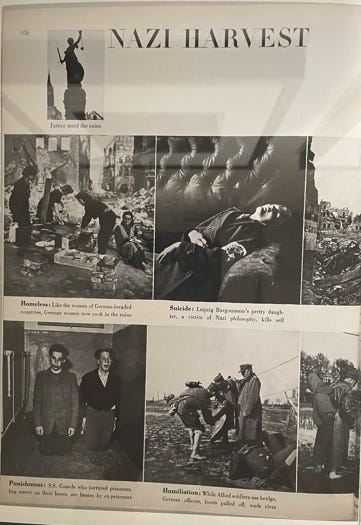

In Paris two years ago, I saw the exhibit “Women War Photographers” at the Museum of the Liberation of Paris. It included some of the spreads Lee Miller did for Vogue, her words and photographs filling the pages, shocking the world with their candid portrait of the war.

Lee Miller’s final decades were spent in the peaceful Sussex countryside at Farley Farm. The house is now a museum and it also houses the Lee Miller Archives. I’m dying to go there. Right now they have an exhibit of Miller’s original photographs next to reproductions done for the film Lee with Kate Winslet. It ends on October 31.

For those of us who can’t make it in person, the Instagram account of the archives can serve as somewhat of a substitute. There are also some interesting interviews with her son. And the V&A Museum has done a fascinating short video about Lee Miller, with commentary by her granddaughter.

Finally, a quote I love from Lee Miller:

"As for me, I frankly don’t know what I want, unless it is to ‘have my cake and eat it’. I want the Utopian combination of security and freedom and emotionally I need to be completely absorbed in some work or in a man I love. I think the first thing for me to do is take or make freedom - which will give me the opportunity to become concentrated again, and just hope that some sort of security follows - even if it doesn’t the struggle will keep me awake and alive."— From a letter to Aziz Eloui Bey. November 1938

I’d love to hear your thoughts—about Lee Miller, this incredible quote, the Kate Winslet film, or anything else on your mind. Is there a particular artist or writer, or a book or film inspiring you these days?

All the best,

Anne

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please click on the heart at the bottom or the top of this email/post. It helps others discover Audacious Women, Creative Lives. And makes me super happy!

Stimulating post. I knew about Lee Miller before seeing the film, but it told me much more, of course. Both my daughter and her son (18) loved it and I think for them, the real interest was seeing WWII and especially the concentration camps brought to life so vividly. Almost all people of my generation (I am 82) will have seen the horrible pictures from the camps at some point in their lives, but perhaps this is less so for younger people.

But what interests me more in your post is the issue of women wanting to be their own person with a creative life and wanting close relationships – and, for many, including me, children..This is a problem for women (indeed, all couples) in all sorts of situations. We all struggle with it and we always will. Sometimes I think creative people see it as particularly important in their case, but it is equally true for the many women who find fulfilment in other sorts of jobs. If "grief is the price we pay for love", then that conflict is the price we pay for a rich and fulfilling life. And often it is the children who suffer.

Thanks for your post about Lee Miller. I hadn’t heard about the novel and look forward to reading it. About the film: I enjoyed the opening because the languid, sun-drenched exhibitionism and sensuality contrasted so greatly with the later scenes of deprivation and danger and discomfort during wartime. It contained a very basic structure of story-telling: the reversal. We need more stories like this of women who have a mission and passion that cast aside societal expectations. In some small way I felt that when I was researching my first novel in Guatemala during the civil war. I was obsessed with it. I haven’t felt such passion for my subject matter since then. I didn’t choose that path; it chose me. For six years I traveled back and forth to Central America to do the research and I never felt more alive. I am so grateful for the movie “Lee” because it rekindled that feeling in me and made feel a part of something larger than myself.