This week is a roundup of some things I’ve been digesting lately. I hope you find some food for thought here.

This newsletter is free for all. Sign up so you won’t miss a post, if you haven’t already.

As I revisit books I loved for my fiction workshop, I’m re-reading After You’d Gone by Maggie O’Farrell. Its basic theme is wrapped up in two formative conversations the protagonist, Alice, has early in the book.

#1) With her grandmother when Alice is young and wishing she were pretty or talented and feeling like she is worthless: “‘Alice, I’ll tell you a secret. In here,’ she pressed her hand against my solar plexus, ‘right here, you have a reservoir of love and passion to give someone. You have such a huge capacity for love. Not everyone does, you know.’”

#2) With her mother, shortly after Alice has started dating someone: “Alice, I’m not getting at you. You can see who you like. . . I just can’t bear to see you letting passion impair your judgment. Don’t ever let all this being in love stuff obscure your sense of self-preservation.”

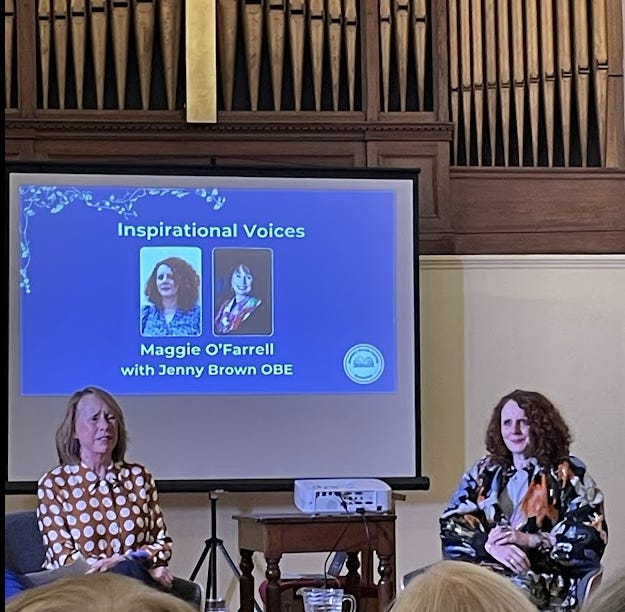

And there you have the central conflict of the novel. It’s an engrossing read as you untangle how mother and daughter follow different, but related, romantic paths in life. It gutted me when I first read it. And I recently had the chance to tell Maggie O’Farrell that.

I was thrilled to see her at the Women’s Fiction Festival in Edinburgh. (Mark your calendars for next year!) During the Q&A, I asked what inspired After You’d Gone, her first novel, and she couldn’t remember—it had been 25 years! But she had some lovely things to say about how hard it was to write and how lost she felt doing it and how it had about seven different plot lines until an agent told her to pare it down to two. I was grateful that she shared her early travails. She became a little more human to me, which is helpful when meeting a writer you admire.

I went to another author event recently with Paula Hawkins, whose new thriller, The Blue Hour, is about a woman artist. I’m currently devouring it. During the Q&A, at Portobello Books in Edinburgh, I asked about the research she did, and she talked about the various artists who inspired her character. What a list it is!

Joan Eardley

Ceila Paul, whose memoirs Hawkins read. (She’s written Letters to Gwen John and Self-Portrait, both of which wrestle with her relationship with Lucien Freud.)

The article linked in the caption includes this nugget:

“The dialogue around classing women artists as the muses of the more famous men simply because of their relative standing has been buzzing for decades. But right now—especially in the context of today, when women are digitally yoked to their male lovers even as they are trying to break free of that collocation—it is getting specific attention.

“At the end of October, Guardian journalist Rhiannon Lucy Coslett wrote a twitter thread in response to the plugging of the touring Dora Maar retrospective: “I really feel very strongly (and see also Lee Krasner) that the only way women artists can begin to be respected and appreciated on their own merit is to stop using the names of men they slept with in headlines for articles about them […] by repeatedly invoking the men they slept with you are in a sense minimising them again while claiming to righteously raise them up”.

Barbara Hepworth (I saw her home/museum in St. Ives, Cornwall, almost exactly one year ago and loved it! I hadn’t known Hepworth, who is huge in Britain.)

Lee Krasner (wife of a famous painter whose name I won’t mention :)—See Guardian article about her emerging from his shadow, finally.

Louise Bourgeois (I saw this sculpture, one of her many spiders, so many times over the years at the New Orleans Museum of Art, and I had no idea who she was. Now I know and I am smitten!)

Speaking of Louise Bourgeois, I read this in “The Marginalian” by Maria Popova, which I stumbled upon when googling something or other:

“You are born alone. You die alone. The value of the space in between is trust and love.” (from Louise Bourgeois, Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923–1997)

I had taken a picture of the quote weeks ago and found it on my phone again recently. It struck me when I first read it, and then hit me harder this time. Two people I care about are currently facing a parent’s mortality, and I know how hard my father’s death hit me (back in 2015), so I’ve been thinking a lot about what they must be going through right now. And, of course, I can’t help thinking of the mortality we all must face—ultimately alone. But now, we are living, and without love and trust, we aren’t fully living, I think.

For some reason, Bourgeois’s quote is always used to illustrate her ideas about the importance of solitude for the artist, but to me it says something different. I’d love to hear your thoughts, if you have any. I’ve had a lot of thoughts on the subject, which I wrote about here:

These thoughts about mortality also reminded me of something I heard

say at another author event I went to a Portobello Books a couple of weeks ago. I’m new to his work, but I was so blown away by him that I picked up his last, Cleanness, and look forward to reading the new one, Small Rain. He was such a generous, thoughtful speaker, and I envied one of his former students, who was sitting in the audience. (Plus, there was the cutest little doggie in front of me. Garth was clearly smitten with her as well.)About his new book, Garth said (roughly quoted),

“Any life devoted to something (like art, poetry), as with the case of the narrator of Small Rain, is a gamble.”

The situation of Small Rain is that the narrator gets very ill and faces his mortality, which leads him to confront the question of whether or not the gamble paid off. Behind the whole book is the question, “Can art/poetry help us live?” And, by extension, help us die. What do you think? It’s a big, juicy question. (Garth also has a beautiful Substack newsletter, “To a Green Thought.”

Lastly, I’ll leave you with a poem from Kay Boyle, whose work I’ve been returning to as well lately. If you don’t know who she is, go back to this post from last month:

Two Audacious Women Writers Who Made Me Want to Change My Life

Here’s the poem:

“Advice to the Old”

Do not speak of yourself (for God’s sake) even when asked.

Do not dwell on other times as different from the time

Whose air we breathe; or recall books with broken spines

Whose titles died with the old dreams. Do not resort to

An alphabet of gnarled pain, but speak of the lark’s wing

Unbroken, still fluent as the tongue. Call out the names of stars

Until their metal clangs in the enormous dark. Yodel your way

Through fields where the dew weeps, but not you, not you.

Have no communion with despair; and, at the end,

Take the old fury in your empty arms, sever its veins,

And bear it fiercely, fiercely to the wild beast’s lair.

Let us know in the comments what resonated with you, what thoughts jiggled loose as you read this bric-a-brac of thoughts. I always love to know what you’re thinking! (Even if I can’t always respond to everyone.)

All the best,

Anne

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please click on the heart at the bottom or the top of this email/post. It helps others discover Audacious Women, Creative Lives. And makes me super happy!

As always, I find your blog inspirational and thought provoking. This will float around in my brain rent free this week as I tend to requirements and responsibilities, but it will be a welcome renter.

I found Octavia Bright’s memoir, ‘This ragged Grace’ really interesting for her engagement with Bourgeois