Two Audacious Women Writers Who Made Me Want to Change My Life

. . . Because they lived as passionately they wrote.

There are some people who make us impatient with the status quo—who dare to live audaciously and make us start to imagine other ways of being in the world. They are called by psychologists, I recently learned, “expanders.” They help expand our ideas of what is possible. When I came up with the title for this newsletter, it was such women I had in mind.

This newsletter is free for all. Sign up so you won’t miss a post, if you haven’t already.

I’ve known some wonderful expanders, and others I’ve only met through their writings. I want to tell you about the two writers who most particularly made me want to live a different life. One of them you know. The other you’ve probably never heard of.

In those final years of my old life, their words and their lives made me want to be more like them. It’s as if they held out their hands to me and said, “Jump!”

This is why literature is dangerous. This is why women weren’t supposed to read novels in the 19th century. Because they would strain against the leashes of their dull lives. Because they would run off with strange men, like Emma Bovary did.

Frankly, this is why books are banned—because they show us that there are other ways of living than the accepted status quo. They give us ideas.

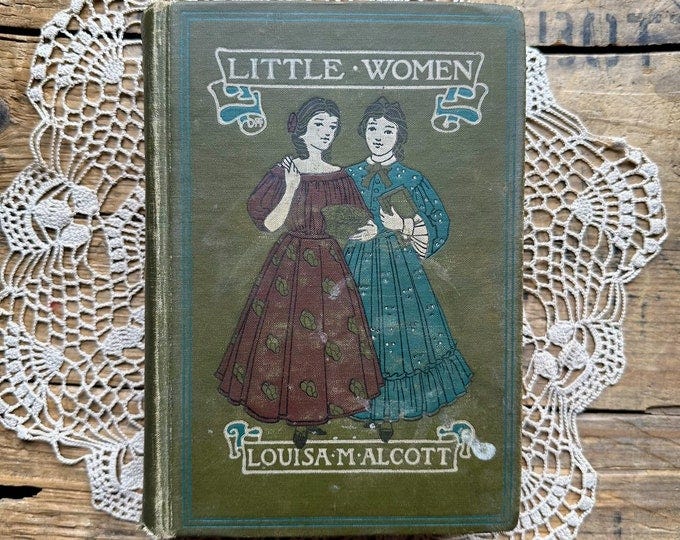

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott has never been banned in the U.S., to my knowledge, but it has given readers a lot of ideas and been one of the most influential books in the world on women’s lives. For generations, girls read it and wanted to be like Jo March—to be tomboys and read books all day and write in their attics. Jo allowed girls to see themselves as individuals with something important to say to the world.1

In a way, Little Women inspired my past life. When I first read it in graduate school (rather late, I know), I was in my early twenties, and it helped me imagine a life as a writer and a mother, which was a big deal for me. Near the end of the novel, Jo says she hopes to write a good book yet, and she thinks it will actually be better because of her family life. That was a new idea to me! And it stuck with me in the coming years as I completed my degree, became a professor, got married, and had a kid.

But the two writers I want to talk about today inspired me to take a further leap into my new life, once my daughter was grown. (I gave her the middle name Josephine, by the way.)

The One You Know

In modern times, Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love has been just as influential for women as Little Women was for earlier generations of girls. In fact, to celebrate its 10th anniversary, a whole volume of readers’ essays was published under title Eat Pray Love Made Me Do It. In the introduction, Gilbert says she has been awed by the impact her story has had on readers. She explains,

It was never really about eating pizza in Italy or meditating in India or falling in love in Bali. It wasn’t about travel or spirituality or divorce. No, Eat Pray Love was about what happens when one human being realizes that her life doesn’t have to look like this anymore—that everything (including herself) can be changed. After that realization occurs, nothing will ever be the same again.

The idea that you could change your life, however hard that may be, was a revelation—and a revolution!

I first read Eat Pray Love when I taught it in a course on American Women’s Travel Narratives in Cork, Ireland, in the summer of 2015. My students’ reactions were mixed. But I understood the hype.

Even though my daughter was only eleven, and having my own adventure seemed impossible, I can see now that it planted a seed. In the coming years we had adventures together as I taught elsewhere in Europe—and I began to dream of having my own again once she was grown.

In my final years of teaching, I returned to Eat Pray Love, incorporating it into my American Women’s Life Stories class. I had created a section on travel, because leaving home has always been an important way for women to get outside of their everyday lives and imagine other ways of being in the world. And I wanted my students to see what was possible for themselves as well.

I don’t know whether it had a lasting impact on any of them, but I was becoming ready for change—big change. As I began to see, with Gilbert’s help, that the signature of the universe—of life itself—is change, a spark of hope was lit.

Life doesn’t always have to be like this. I can think of no more powerful message for women of any era to hear.

The One You Don’t Know

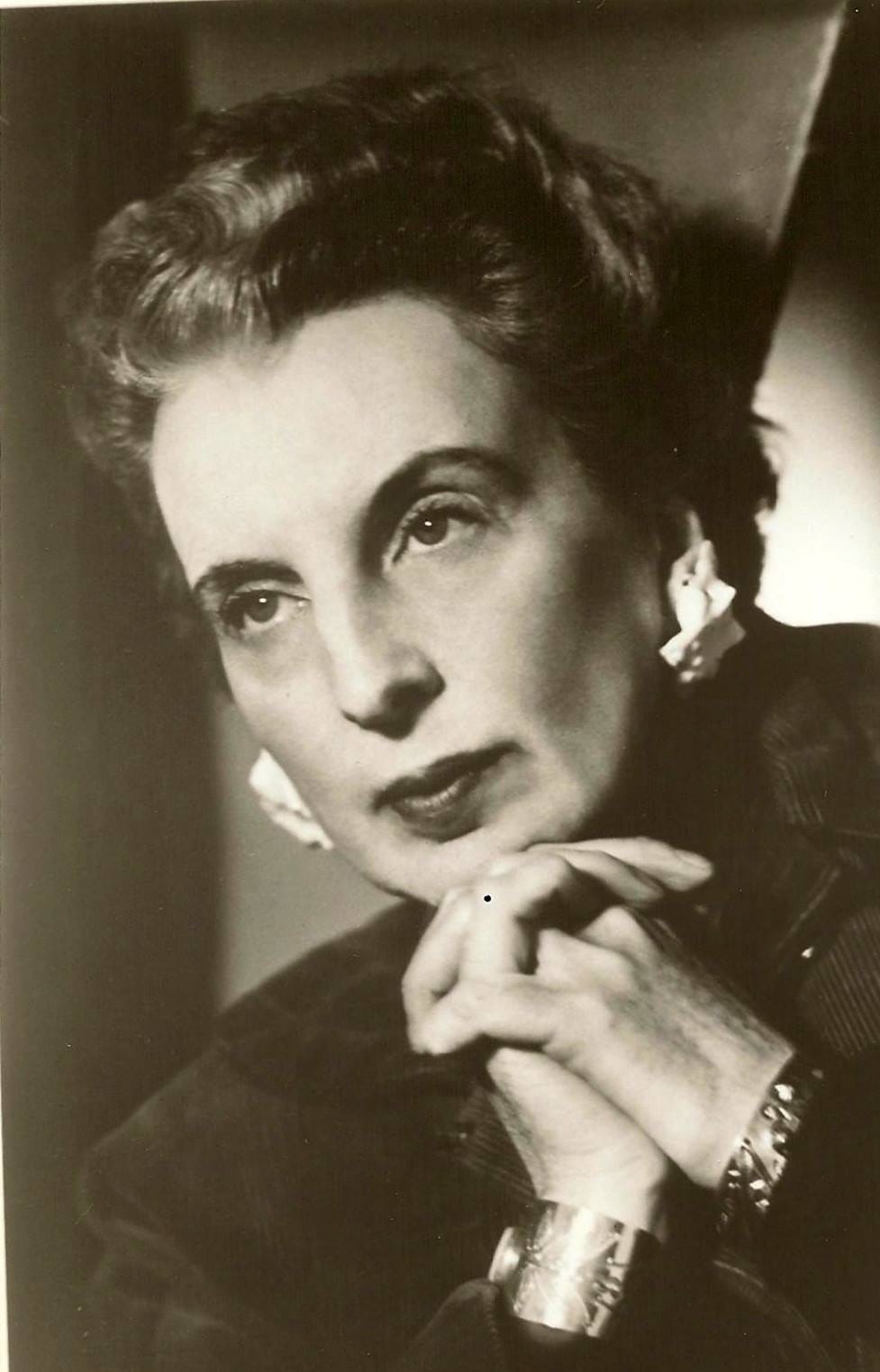

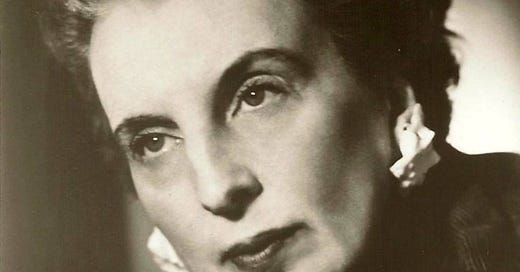

So who was this second woman who made me want to live a different life? She came into my life two years after that summer in Ireland, when I was teaching a course in Austria on the Short Story in Europe. I was looking for a woman writer from the Lost Generation in the 1920s to group with Hemingway and Fitzgerald.

And into my life walked Kay Boyle. She wrote about those days in Paris,

Our daily revolt was against literary pretentiousness, against weary, dreary rhetoric, against out-worn literary conventions. We called our protest ‘the revolution of the word,’ and there is no doubt that it was high time such a revolution took place.

She hung out with Joyce, Beckett, Stein, and all the rest. She “knew everyone and saw it all,” her biographer, Sandra Spanier, has written.

Although she was still in her twenties when she came to Paris determined to make a new life as a writer, she had already lived a lot. She had married a Frenchman, had an affair with a passionate American poet dying of tuberculosis, given birth to his child after his death, and tried and failed to be happy with her husband again. She wanted to live passionately and she wanted to write, so she bundled up her daughter and headed for Paris. (She was probably the only single mother of the so-called Lost Generation.)

That was just the beginning of Kay’s full-to-bursting life. After the stock market crashed, when most Americans left France, she stayed and married the “King of Bohemia,” the artist and writer Laurence Vail (who was recently divorced from Peggy Guggenheim). They lived with their growing brood of children in the South of France and then moved to the Austrian Alps, where they witnessed the rise of Nazism.

When the war started, they were living in the French Alps. After the German invasion, she fell in love with an Austrian refuge of the Nazis and helped him to escape to America. In mid-1941, she, Laurence, and the children fled Europe on a Pan Am Clipper out of Lisbon with Peggy and Max Ernst.

Back in the U.S., Kay divorced Laurence and married her Austrian lover, Joseph von Franckenstein, who would later become a spy for the Americans and help liberate his home country from the Nazis. You can’t make this stuff up!

In later years, Kay and Joseph would stand up to Joseph McCarthy and the FBI when they accused her of being a Communist. And after his death, she would march with students on strike at San Francisco State University in 1968, standing between them and the police. She would be a passionate advocate for Amnesty International and persecuted writers all over the world for the rest of her life.2

And she was an amazing writer! She not only chronicled Europe’s fall into madness and its postwar recovery, but she also helped shape the modern short story as a regular contributor to The New Yorker and the winner of two O. Henry awards for the best short story of the year.3

For five years, I researched Kay Boyle’s life and work and began writing a biography. I was awed by how deeply she lived, how full her life had been. I wanted to write that life, to live it vicariously. But the more research I did, the louder the voice inside my head grew. It kept saying, How will you know, when you are on your deathbed, that you have really lived?

I could never live as fully as Kay did. She lived passionately right out of the gate, while I had taken a safer route. But I wanted the rest of my life to feel more like hers—full of passion, committed to art, plumbing the depths of the soul, living and writing as if every day could be the last—because it could. And you don’t have to be living in the midst of a war to realize that. (For me, as I have written before, it was the death of my much younger brother that did it.)

I’ll end with a quote from Elizabeth Gilbert that for me sums up what both of these women represent to me. I heard her say this on a podcast about the idea that motivated her novel City of Girls:

“The idea of a woman standing in her own full desire, looking out into landscape, seeing something that she wants and being like, I’m going to go get that.”4

That is absolutely revolutionary!

Now, I’d love to know who your “expanders” have been. Who are the women who have given you hope, inspired you, or helped you imagine other possibilities in your life?

I can’t wait to see you in the comments!

--Anne

P.S. If you enjoyed this post, please click on the heart at the bottom or the top of this email/post. It helps others discover Audacious Women, Creative Lives. And makes me super happy!

Just two incidences of this: In Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, two girls from 1950s Naples decide after reading Little Women that they want to grow up and be authors. One of them is able to break out of their lower-class neighborhood and do so. Another example from recent-day Pakistan was on “This American Life” a few years ago. It was a riveting listen.

Marianne Goldsmith, one of Kay’s students, has written about her activism for Literary Hub.

You can learn more about her at the Kay Boyle Society.

It's unbelievable, how a woman like Kay Boyle isn't a known star in the firmament of deservedly illustrious ones. Thanks for shining a light on her. For me the book West With the Night by Beryl Markham was transformative. And I'd definitely add Cheryl Strayed to my list. I have a sister-in-law who is an adventure guide, doing one of the most dangerous jobs on earth, she is one of the most inspirational women I've ever met and I'm eternally pestering her to make a book of her illustrated journals.

I’m grateful to you, Anne, for sending my mind off in this direction this early morning.

A brief bio of Katherine Anne Porter states: “Often concerned with the themes of justice, betrayal, and the unforgiving nature of the human race, Porter’s writings occupied the space where the personal and political meet.” I saw Porter read when I was in my early twenties and just beginning to try on “writer” as part of my identity. She was in her eighties, elegant in a white suit and emerald jewelry. I read her stories and tucked away that image of her at the reading, being bold and audaciously proud. One has to take on that mantle of authority at readings. Over the years I have probably given a hundred readings or more. It requires projecting your voice and believing that what you have to say is worth the audience’s attention. I think of her often. She had a hard life when it came to family and romance. She was married four times. She might have been better off if she had realized early on that she was married to her work. After three marriages, that’s what I finally decided. Women can do that now! But in Porter’s generation it was harder to be that audacious.

The other woman who comes to mind is Georgia O’Keeffe. She married Steiglitz but then she went away from him and NYC and moved to New Mexico, the place that deeply fed her art. There are so many wonderful photos of her that exemplify her adventurous spirit. In the one I love, she’s sitting on a motorcycle somewhere in New Mexico. This was at a time when it probably took a long day’s ride or drive or longer to get from Santa Fe to Abiquiu, where she made her home. I admired her single-mindedness about her art. When I was finishing my first novel — HUMMINGBIRD HOUSE — I rented an adobe house out that way for six months. After writing I would often walk the trails at Ghost Ranch and I allowed myself to feel a kinship with Georgia. It kept me going.